From BAT to AsyncRAT

While perusing public samples from the Triage database, I stumbled across an interesting payload that was labelled as AsyncRAT. AsyncRAT is an open-source Remote Access Tool (or Trojan may be more apt) written in C#, so I was curious as to what the infection process would look like starting as a Windows Batch file. For anyone who wants to follow along, the sample on Triage can be found here.

Initial Payload

Upon first investigation, the batch file appears to be heavily obfuscated, but upon closer inspection, the behavior exhibited isn’t too difficult to interpret. The file starts off with a set "gXtM=set ", which effectively creates an environment variable called gXtM with a value of set . The following lines use this gXtM variable in %, denoting to the Windows commandline interpreter to use the environment variable named gXtM. These commands set more environment variables. At the end of the batch file, all of these environment variables are then combined together to create the payload.

To decipher these concatenated environment variables, I used the batch_deobfuscator script from DissectMalware on GitHub. Running the script against the batch file produces the following deobufscated code.

| |

NOTE: The batch_deobfuscator script seems to use script.bat as the name of the input file, so if this script is run against the payload, all filename-based variables will be script.bat instead of the actual name of the file.

First, the batch file copies the powershell.exe binary to <filename>.exe, where <filename> is the name of the batch file. It then uses ~nx0, which in batch terms means the name of the current batch file, and combines it with .exe to get the name of the newly copied powershell.exe binary. From here, it runs a large PowerShell command.

PowerShell Payload

Copying the -command portion of the PowerShell payload and cleaning it up a bit reveals the following:

| |

This command does a number of things. First, it queries the original batch file, payload.bat, for lines that start with “::”. If we look back at the original batch file, we can see a large line that starts with the “::” character. The PowerShell command takes the Base64-encoded blob on this line and decodes it. This decoded value is also encrypted with AES-CBC, so the command then decrypts the value with the specified encryption key and IV (also Base64-encoded). Finally, this latest value is compressed with the gzip data format, so it also decompresses it. At this point, the script has the actual payload that was contained within the batch file, which it then loads into the process and executes it.

While we could perform all the required steps (Base64 decode, AES decrypt, and GZIP decompress) manually, why not let the script do it for us? To achieve this, we start by commenting out the final three lines of the payload; this is the portion that loads the payload into memory, which we definitely do not want to happen. Instead, we can redirect it to a file using the Set-Content cmdlet. Further steps need to be taken to make the script work, including formatting the .NET classes appropriately. The final script looks like the following:

| |

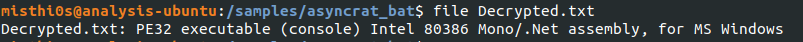

Running the file command against this newly created file (Decrypted.txt in my example) shows us that this is a .NET executable!

.NET Executable

Since this is a .NET executable, let’s load this up in dnSpy. Looking at the code, there’s a few things that jump out. There’s a few functions that perform similar activity as the PowerShell script; specifically, there’s a function to decrypt an AES-CBC input, and there’s a function to decompress a GZIP data input. There’s also a number of string values that appear to have Base64-encoded payloads in them. Let’s look at those more closely.

In the case of this sample, the function JLUpOCopNzUYcmWAAVqD appears to be used to decrypt an AES CBC ciphertext block. Below is the code for the function:

| |

The function requires three inputs: the encrypted data, the encryption key, and the IV used. Let’s look at one of those Base64 encoded strings. Here’s an example of one of them, string3, from the payload:

| |

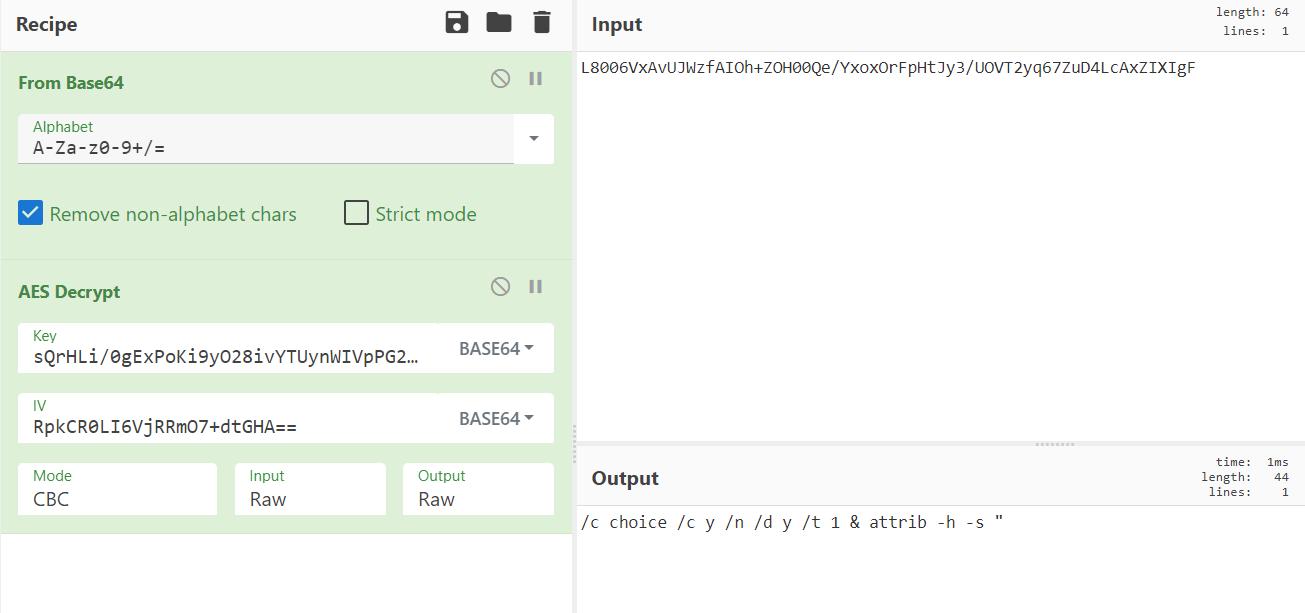

If we look closely, we can see mention of the JLUpOCopNzUYcmWAAVqD encryption function; it also looks like it is providing the three inputs required for the function, just in Base64 format. In this instance, that would mean that the L8006VxAvUJWzfAIOh+ZOH00Qe/YxoxOrFpHtJy3/UOVT2yq67ZuD4LcAxZIXIgF encoded value is the encrypted text, the sQrHLi/0gExPoKi9yO28ivYTUynWIVpPG22IRqfJx6w= encoded text is the encryption key, and RpkCR0LI6VjRRmO7+dtGHA== is the encoded IV.

With these values, we can manually decrypt the encrypted payload to see what is there. CyberChef is an excellent tool to do this. We need to start with Base64-decoding the input string, then using the AES Decrypt function, with the appropriate key and IV, to decrypt the payload. All of that plugged into CyberChef will look like the following:

The encrypted text was successfully decrypted! The decrypted content is the following: /c choice /c y /n /d y /t 1 & attrib -h -s ". Based on the code where this string is used, the above effectively means that a cmd.exe process will be used to first sleep for a second (due to the choice command, which is a very common technique used by threat actors to sleep payloads for X seconds) and then modify the payload to remove the hidden and system attributes. Below is the code where this occurs, which also shows us that the cmd.exe process then deletes the payload file, likely in an attempt to hide its tracks:

| |

There are quite a few strings in the payload that go through this decryption process so, like before, why not let dnSpy do the heavy lifting?

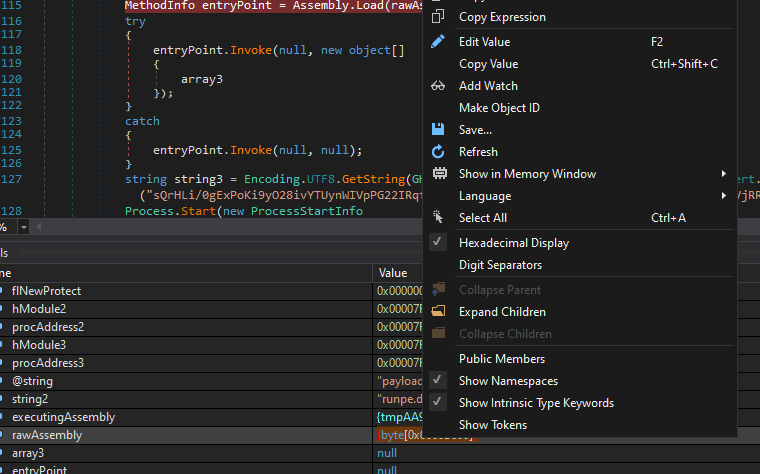

By running the dnSpy Debugger, and breaking at the entry point, we can follow the execution process and see the decrypted values as they are decrypted. While doing this on my VM, every run of dnSpy ended on line 125, which appears to make the program hang until killed. This is likely due to anti-debugging techniques in the payload, but at this point in the execution, we have what we need next.

In this instance, the most important part of this payload is the rawAssembly variable. Once this is decrypted, it produces a large byte array of data that is set to be loaded into the process with the Assembly.Load method, similar to the previous PowerShell payload. This makes the rawAssembly content a potentially valuable piece of the puzzle.

Once the variable has been decrypted in dnSpy, simply right-clicking on the value and clicking “Save” will let us output the contents of the byte array to a file.

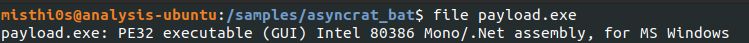

Let’s take a look at what this file is with the ever useful file command.

Another .NET binary! Let’s open this one up in dnSpy as well.

Final Payload

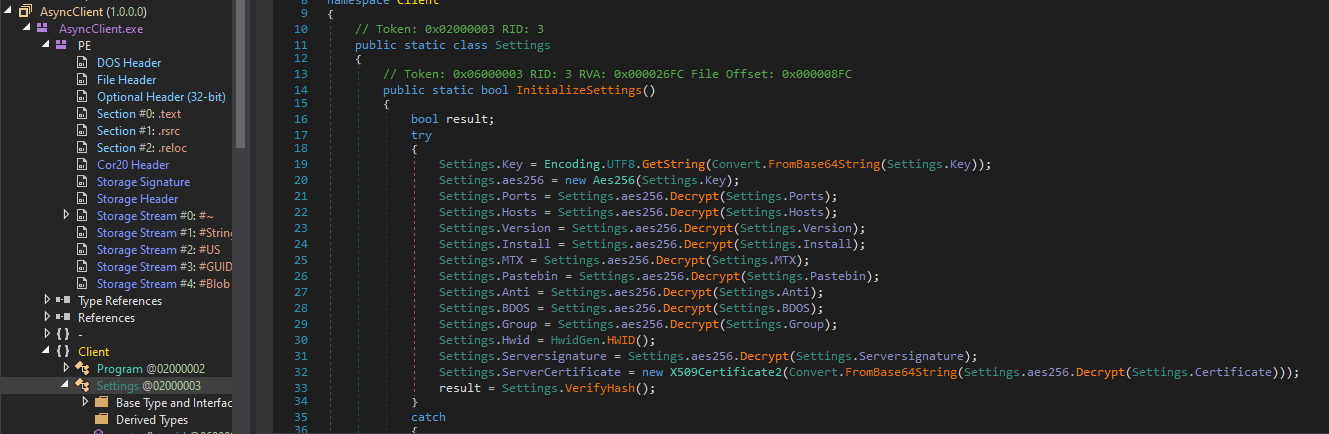

Upon loading this into dnSpy, I can immediately tell that this is an AsyncRAT payload. This is due to the the assembly being named “AsyncClient”, which is the internal name for the AsyncRAT payloads, as well as the formattting of the Settings class.

AsyncRAT encrypts configuration data, such as C2 server names, ports, pastebin configuration settings, etc, in its settings. The encryption key is also located in this Settings class, giving us everything we need to decrypt the configuration. I was able to find a nice Python script in an article on eln0ty’s blog that allows for an easy way to decrypt AsyncRAT configs. All we need to do is replace the key variable, as well as all of the config items with the values in our sample. Below is a copy of the script containing the necessary values for our sample:

| |

Running the script gives us the cleartext configuration settings for this AsyncRAT sample!

| |

So… Infection Vector?

After analyzing this malware sample, I did some Googling to see if I can find more information on it. I stumbled across a tweet from Unit42 and a blog post from Rapid7 with similar looking samples. In these cases, it appears that Redline Stealer was the final payload, but the infection process was pretty much exactly the same; the Rapid7 blog also mentions that they have also seen AsyncRAT payloads being used with this method. The articles outline a relatively new technique being used by threat actors where they use OneNote files to deliver malicious payloads. Based on this information, I strongly believe that this batch file payload originated from within a OneNote file used by the (currently) unknown threat actor in this campaign.

Thanks for reading!!

IOCs

Files

| Filename | SHA256 Hash |

|---|---|

| payload.bat | a15f29572a149a04d45b8c01daa047ec9f517077a507f8d53ac9b8a8ceed4a34 |

| loader.exe | 542d0b1b95f943e9718082c790141b156812f851b9f9dc9445d57653486a6702 |

| AsyncRAT.exe | 97e6c937b6768d111c4a94bd993c04cb4069da146423ea69d2af20d301057295 |

Domains

| Domain | IP Address |

|---|---|

| churchmon.ddns.net | 89.117.21.144 |

| churchmon21.ddns.net | N/A |

| churchmon22.ddns.net | N/A |